The Terafactory

Can we revolutionize the built world with lessons from Apple and Tesla?

In the past decade two inventions have redefined the boundaries of technological innovation and economic value: the iPhone and the Tesla Model 3. These products are not just marvels of engineering and design; they are paragons of cost optimization. Their success lies in a maniacal focus on cost-engineering down to the component level, coupled with unparalleled supply chain scale and efficiency. By applying similar principles to the real estate industry, could we fundamentally transform how buildings are built? Could we create a system as efficient and scalable as the assembly lines that produce our favorite devices and cars?

Apple: The Masterclass in Supply Chain Efficiency

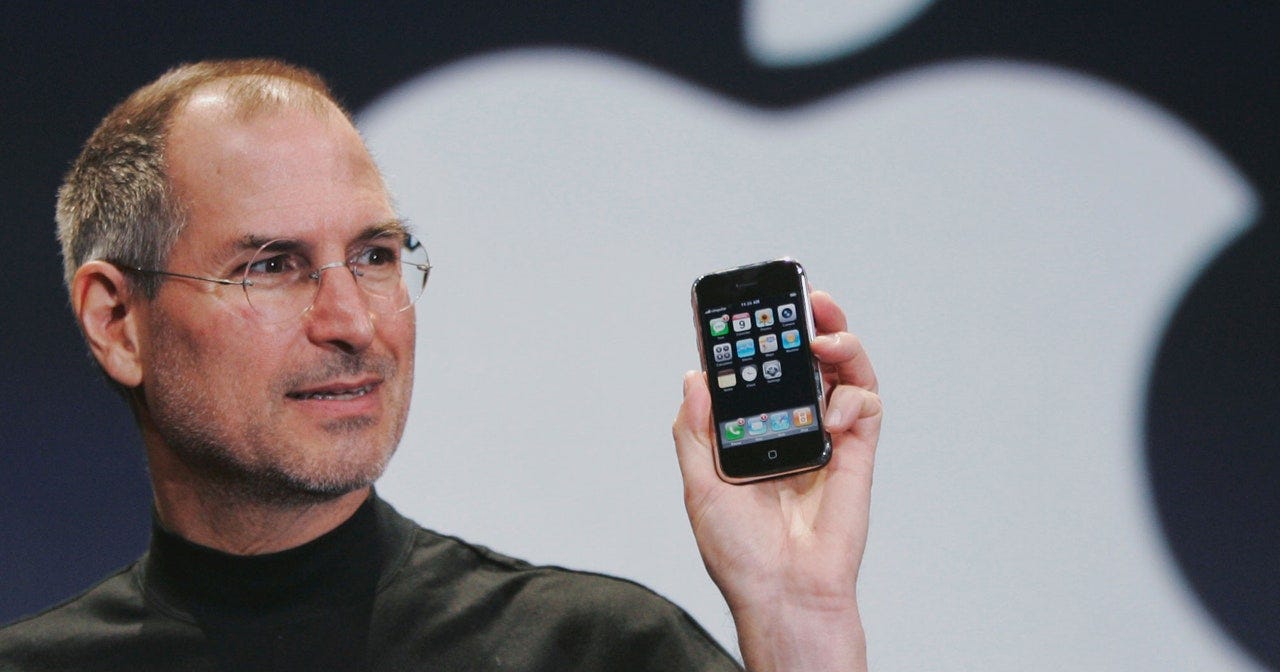

When Steve Jobs introduced the iPhone in 2007, it was a complete reimagination of the mobile phone. Curved Corning glass corner-to-corner (yes that redundancy is intentional), full-touch interface, phone/ipod/camera/internet browser all-in-one. None of this stuff had been done before, so it not only had to be designed for the first time; the machine that built the machines would have to be built. If the supply chain wasn’t appropriately efficient, the end-product would be cost-prohibitive. Apple’s ability to offer a premium product at a relatively accessible price stems from its meticulous attention to every detail, down to the sourcing of materials. Jobs, followed by Tim Cook, who became Apple’s CEO in 2011, revolutionized how a company could control its production processes.

Apple’s supply chain is a finely tuned machine, optimized to ensure that every component of the iPhone, from the A-series chips to the precision-engineered glass, is produced at the highest quality and lowest possible cost. Cook, a logistics wizard, implemented strategies that included securing long-term contracts with key suppliers, investing in advanced manufacturing technologies, and even locking down exclusive rights to essential materials. These moves ensured that Apple could produce devices at scale without compromising on quality or inflating costs, resulting in a product that offers extraordinary value. Basically - under Jobs’ vision, they put a phone into everyday people’s hands that was so sophisticated, they probably had no business owning in the first place. Henry Ford type shit.

Tesla - Taking the Next Step

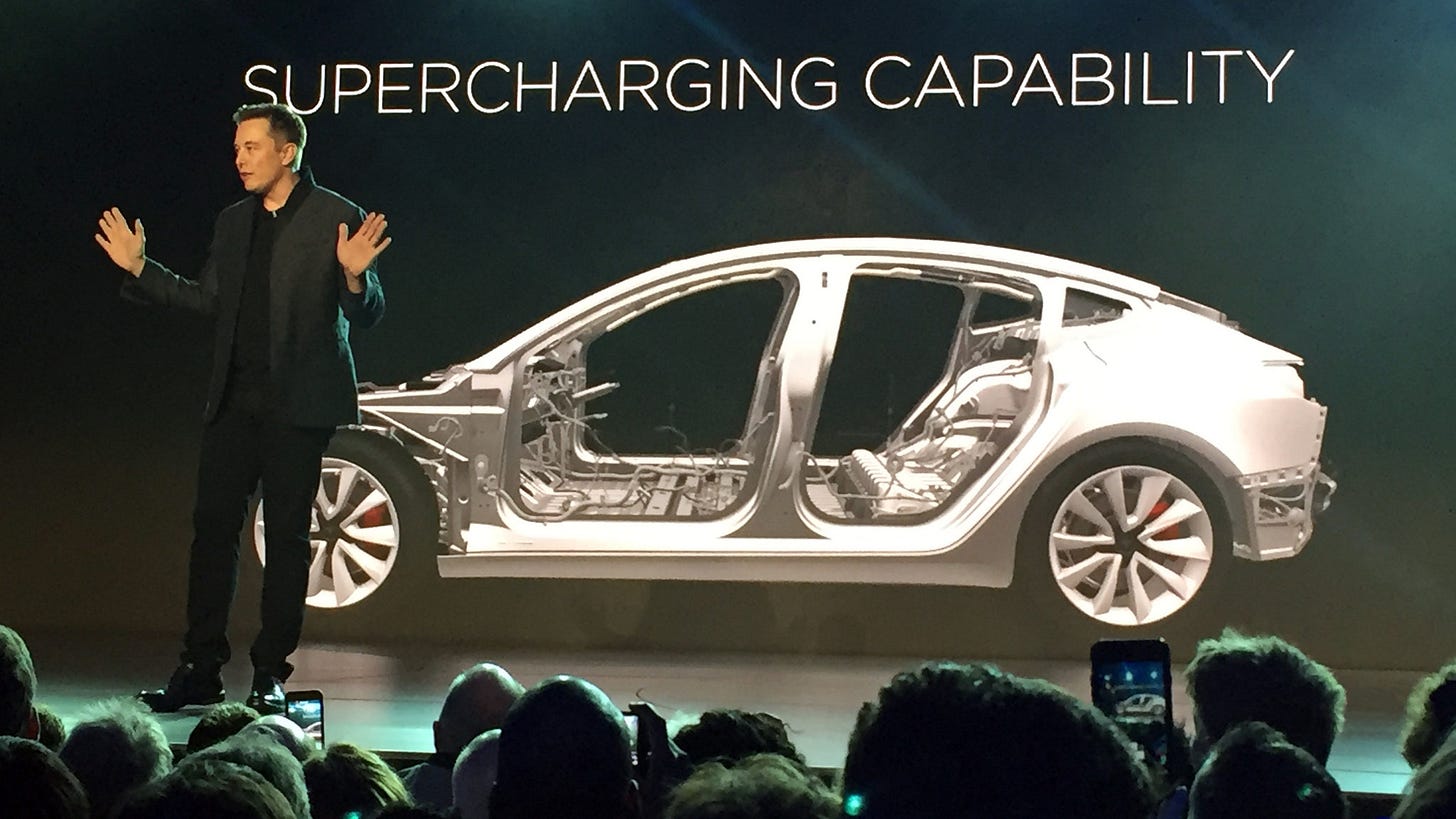

In the world of Tesla, led by the visionary Elon Musk, vertical integration isn't just a buzzword; it's the backbone of their strategy, also reminiscent of the industrial might of Henry Ford, but tailored for today's electric era. This approach has manifested in unique and sometimes quirky ways, as detailed by Walter Isaacson in his exploration of Musk's leadership at Tesla.

One of the most emblematic examples of Tesla's vertical integration strategy during high-pressure times was the decision to literally raise tents around their Fremont factory. This wasn't a stopgap; it was a symbol of Musk's adaptive manufacturing philosophy. When the Model 3 production needed to be accelerated, these tents became makeshift assembly lines, showcasing Tesla's ability to think and act outside traditional constraints. Here, in these tents and under one roof, Tesla's workforce, driven by Musk's relentless push for innovation, worked to increase output, embodying the very essence of vertical integration by being both the problem identifiers and the solution providers. Musk was there personally to push.

Tesla's vertical integration strategy extends far beyond mere production acceleration. The Gigafactory, a collaboration with Panasonic in Nevada, epitomizes this approach. The strategy is about controlling the supply chain for what Musk knows will become the heart of electric vehicles. This factory was designed to produce batteries at a scale that would dramatically cut costs, making electric mobility more feasible; and safer, and lighter, and super convenient because the batteries last longer, oh AND financially attractive. AFFORDABLE.

But Tesla's control doesn't stop at batteries. They've taken manufacturing in-house, designing the machines that make the cars. This includes everything from the motors to the intricate power electronics. Isaacson highlights Musk's philosophy here—bringing technology development in-house to avoid being limited by external suppliers. This allows Tesla to innovate at a pace where traditional automotive strategies lag, adapting and evolving at every stage of production.

Software development, too, falls under Tesla's dominion. Musk's Silicon Valley ethos meant developing software internally, which was crucial for Tesla's vehicles. The over-the-air updates and the development of autonomous driving software have given Tesla an edge, not just technologically but in how they control the vehicle's evolution over time. The thing can drive itself! The only other way to get that on the market today is to call a Waymo. You can’t OWN the Jaguar Waymo picks you up in, Musk is taking that same technology and making it accessible to the whole world.

When it comes to sales and service, Tesla again breaks from tradition by selling directly to consumers. This direct-to-consumer model eliminates the middleman, reducing costs and giving Tesla complete control over the customer experience. It's a strategy that saves money and builds brand loyalty.

Through these layers of vertical integration, Tesla achieves more than just cost efficiencies or supply chain control. It's about speed, innovation, and the ability to pivot quickly in the face of global challenges like the semiconductor shortage, where Tesla's engineers could redesign parts of their vehicles or software to accommodate different chips, showcasing a flexibility that few competitors can match.

It appears clear to us, and perhaps anyone else who is actually paying attention, that Tesla is simply an order of magnitude more fervent about building amazing technologies AND enabling the entire world with them. Tesla's approach to vertical integration and maniacal cost engineering has allowed it to offer vehicles that, while still premium, compete fiercely on cost-effectiveness over time, especially considering the benefits of electricity over gasoline. This strategy not only insulates Tesla from supply chain risks but also positions it to potentially offer vehicles at lower price points as it scales, aiming to make electric mobility accessible to a broader audience. This aggressive integration and engineering focus has been pivotal in Tesla's rise to be one of the most valuable car companies globally, not just for its technological advancements but for its business model innovation.

The Emergence of a New Business Model

In 2011, Marc Andreesen famously proclaimed ‘software is eating the world.’ The thesis was that software was now the dominant force in transforming industries and reshaping the global economy. He portended that traditional business across every sector would be disrupted or overtaken by software driven companies.

The passing decade has seen the rise of new internet enabled businesses (such as the FAANG stocks) with the biggest winners being the aggregators. These are businesses that don’t create value by controlling scarce resources, but by building exclusive relationships with consumers through aggregating their demand and attention. For example Google has aggregated the demand for search allowing them to force suppliers (media publishers) to adhere to their rules.

This philosophy was expected to extend across the economy as new internet enabled business models would ‘eat the world’ but that plainly hasn’t happened.

In fact, a cursory overview of the sectors of the American economy would note that a large part is still resistant to technological adaptation. Construction and real estate make up 17.4% of the economy and are both examples of industries where the early venture capitalist promise has simply failed.

Image from:

The base truth which Packy McCormick puts plainly is that “producing new physical things…is a physical problem, and it requires physical solutions.” He predicts that the new generation of tech enabled businesses will follow a completely new playbook, deeply embedding technology to create structurally superior unit economics. These companies will be ‘Vertical Integrators’ and are the emerging threat to built world incumbents. A quick glance at the public markets in 2024 seems to corroborate Packy’s simple truth. Vertically integrated hardware and software juggernauts like Microsoft, Tesla, and NVDIA are running away with the lion’s share of S&P market cap; while the pure-play software companies’ multiples have been decimated.

Defining the New Model

One of my favorite quotes is from Mark Twain, in his autobiography he stated “there is no such thing as a new idea. It is impossible. We simply take a lot of old ideas and…make new and curious combinations.”

In the last 250 years there are only two categories where people have had new ideas and made money:

Software

Vertically integrated, complex monopolies.

The younger generations, particularly Gen Z and onward, have grown up in an era where the internet and mobile devices are ubiquitous, shaping their entire worldview. This situation mirrors the turn of the 20th century during the Second Industrial Revolution, when companies like Ford Motor Company, General Electric, and Standard Oil built effective monopolies through strategic integration of new technology and vertical control of their supply chains. These companies exemplified what Peter Thiel describes as "the machine that builds the machine," a concept where complex coordination results in an insurmountable competitive advantage. Thiel, in his book Zero to One: Notes on Startups, emphasizes that "all happy companies are different; every unhappy company is doing the same as other unhappy companies," highlighting the importance of creating something unique rather than just competing in established markets.

Vertical integrators, as defined by Packy McCormick, are companies that:

Integrate multiple cutting-edge-but-proven technologies.

Develop significant in-house capabilities across their technology stack.

Modularize commoditized components while controlling overall system integration.

Compete directly with incumbents.

Offer products that are better, faster, or cheaper, often achieving all three.

These companies face immense risk because while the technologies might be proven, the challenge lies in integrating them into a new system effectively. This need for integration and systemic overhaul is particularly pertinent in industries like real estate and construction, where the delivery system is structurally flawed, and technology adoption is frustratingly slow.

Our prediction aligns with Thiel's insights: the next significant player in PropTech or ConTech might not be a traditional software startup selling services to the industry. Instead, it could be a vertical integrator that fundamentally disrupts the existing delivery paradigm, potentially becoming one of the largest companies ever seen. This approach would resonate with Thiel's advocacy for building monopolies through unique value creation rather than mere competition, as he states, "From the point of view of a founder or entrepreneur, you want your company to always be a monopoly."

Real estate allocators face immense risk. While the technology may be proven, they need to validate that they can integrate them into a new system. Our prediction is that this is what the real estate / construction industry needs. The system of delivery is structurally flawed and the adoption of technology frustratingly low. We predict that the next winner in PropTech / ConTech won’t be a traditional software startup selling to the industry, it will be a vertical integrator effectively disrupting the existing delivery paradigm, and it will be the biggest company the world has ever seen. Period.

The Unique Challenges of the Built World

The real estate and construction industry seems to be structurally incapable of vertical integration. It operates on a fragmented, inefficient model. Unlike the end to end control seen in the production of iPhones or Tesla cars, real estate development involves a myriad of players—capital allocators, developers, general contractors, and subcontractors—each with their own incentives, often at odds with each other.

This makes the value chain a tale of inefficiency. Capital allocators push developers to cut costs, who in turn squeeze general contractors, who then pressure subcontractors. This fragmented approach leads to a "kick the can down the road" mentality, where problems are passed along rather than solved, inflating the final cost to the end consumer. The result is a system where the production of buildings is slow, expensive, and fraught with inefficiencies, and disputes,—an anathema to the streamlined processes of vertical integration. For a new business to transform this order of operations they need to deeply understand the reason for these paradigms.

Fragmented Teams

The construction industry is fragmented vertically. This arises from a 1918 Supreme Court decision which has led to the Spearin Doctrine in construction. It suggests that if a contractor follows the specifications that are provided by an owner / designer precisely, any issues or defects are not their responsibility but of the owner who provided them. This legal apportionment of risk has been a dis-incentivizing factor for the verticalization of building delivery and a reason for the emergence of design-bid-build contracts. This makes it difficult to create a fully integrated system leading to silos of expertise rather than efficient processes.

This vertical fragmentation was further reinforced post World War II by the Federal Acquisition Regulations (FAR), a set of rules governing how the US government purchases goods and services including construction projects. It often requires the use of separate design and construction contracts to foster transparency and competitive bidding leading to the separation of teams, discouraging collaboration due to misaligned goals.

Lack of industry standardization

Construction lacks uniformity. A reason why is that we build mostly unique structures and even if it is the same product (identical house) site conditions, weather or project teams can differ. Construction sites are PHYSICALLY distributed and decentralized, making “scale” in the traditional manufacturing sense, impossible. Sure you can rip a mile-high tower in Jeddah or a box the size of 16 empire state buildings in Riyadh; but hear me when I say this. That’s tiny. It’s tiny compared to what Tesla and Apple have done; and it’s even tinier on the grand scale of real estate development.

Even the largest project sites span various geographies, each with its own permits, building codes, inspection regulations, and building departments. Each site can have unique design requirements shaped by local climate, wind, and seismic conditions.

These constraints have pushed the industry to become capital light and vertically fragmented, preferring to subcontract the actual building work. This structure has inherent value in its flexibility and ability to mitigate risk—developers can scale capacity based on the number of projects which are in the pipeline.

These overall constraints have led to a decentralized industry, where subcontractors, material suppliers or equipment companies serve a local catchment area e.g. the local material quarry. When a builder has a project in a new region, they rely on locally available resources.

This, often taken for granted, is in fact a unique strength of the construction industry. Construction operates through an informal ‘community of practice’, which provides a shared understanding of how buildings should be constructed. This reduces coordination costs and enables new project teams, whom have never worked together, to quickly form.

This informal community is reinforced by laws that require adherence to ‘standard practices.’ Deviation from accepted norms introduces risk and liability, making innovation challenging. New building systems are difficult to implement because process change requires adoption into the ‘community of practice,’ which unofficially governs industry standards. These characteristics—risk apportionment, difficulty in optimizing supply chains, and lack of standardization—highlight the difficulties that vertical integrators have to overcome.

Our First Vertical Integrator: Lessons from Katerra

Brian Potter serves as a Senior Infrastructure Fellow at the Institute for Progress (IFP) and writes the Construction Physics newsletter. He focuses on improving productivity and reducing costs in building construction and has written at length on this topic. He has 15 years of experience as a structural engineer, previously having managed an engineering team at Katerra, a SoftBank-backed construction startup.

Katerra is one of the most well known attempts as a vertical integrator in construction and of those who have tried Brian Potter speaks most highly of their attempt. The vision was to develop standard off the shelf buildings that could be customized for a client's needs the same way mass produced cars offer a wide variety of trim options. Imagine fast-forwarding from coach-built cars to modern cars with “optional extras.”

They designed a series of building products which were mass-produced in their own factories using economies of scale and advanced manufacturing to build more efficiently. The products would have Katerra-supplied materials from lightbulbs to countertops and appliances.

However, Katerra is not a success story in the world of venture. They’re ridiculed, and the reasons for their failure are numerous. If you don’t want to read a damn bullet list, skip it and I’ll tell you in plain English why they really failed.

Overambitious Expansion and Lack of Focus - Katerra tried to tackle too many aspects of the construction industry simultaneously. Instead of focusing on a niche or developing a clear product-market fit, they attempted to integrate every part of the construction process from design to manufacturing to assembly. This led to a dilution of efforts and resources without achieving proficiency in any single area.

Execution Over Vision - While the vision of revolutionizing construction through technology and vertical integration was solid, the execution was lacking. Reports indicate that despite the innovative approach, Katerra struggled with project delivery, often not completing projects on time or at all, which damaged its reputation and business relationships.

High Operational Costs and Financial Mismanagement - The company's strategy required significant capital investment in factories, technology, and acquisitions. The operational model was asset-heavy, which became unsustainable during downturns like economic recessions or the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, there were issues with financial reporting and management, leading to investigations by the SEC.

Dependency on SoftBank Funding - Katerra relied heavily on funding from SoftBank, raising over $2 billion. However, this dependency meant that when SoftBank's investment strategy faced scrutiny or when additional funding was not forthcoming, Katerra was left financially vulnerable. The collapse of Greensill Capital, one of its lenders, further complicated its financial situation.

Cultural Misalignment - The company hired a workforce that was not necessarily prepared for the high-growth, startup environment of Katerra. Many came from traditional construction or tech firms with slower-paced cultures, which didn't mesh well with the rapid scaling and disruptive approach Katerra was trying to implement.

Market and Regulatory Challenges - Construction varies widely by region with different regulations, codes, and market demands. Katerra's one-size-fits-all approach didn't account for these nuances, making it difficult to adapt their standardized solutions to all markets effectively.

Unsustainable Business Model - Katerra aimed to reduce costs by manufacturing components off-site, but the construction industry's complexity and the customization required for each project made it challenging to achieve economies of scale and cost savings. The initial promise of lower prices couldn't be sustained without a clear path to profitability.

Leadership and Management Issues - There were changes in leadership, with the founding CEO Michael Marks being replaced, which might indicate internal strife or a lack of clear direction. The management's inability to address warning signs of failure was also noted.

In short - they lacked fervor in a world with extremely powerful and wealthy incumbents, who stood to lose a lot.

Our Second Vertical Integrator: Incumbent Goldbeck

Goldbeck, now celebrating its 50th year, has revolutionized the construction industry, particularly within the commercial sector, with its innovative delivery of buildings. They've carved out a niche primarily in constructing warehouses, logistics halls, and parking structures, transforming what was once seen as a fragmented process into something akin to an assembly line for buildings.

At the heart of Goldbeck's operation is their control over the entire production chain. Owning 15 factories across the European continent, they've industrialized the construction process. This vertical integration allows them to design in-house with a dedicated team of about 2,500 architects and engineers. What they produce is not just buildings but a "kit of parts," a standardized system of prefabricated components that are then assembled on-site like a giant, functional puzzle. This method promises speed, reduced waste, and a consistent quality that traditional construction often struggles to guarantee.

The company has also developed a unique approach to overcoming the typical uncertainties of construction. Instead of relying on external contractors, Goldbeck deploys their own teams to deliver projects. What's fascinating is they've cultivated a workforce where teams are so well-versed in their standardized methods that they're interchangeable. One team can seamlessly take over from another, ensuring that the project momentum never stalls, much like a relay race where each runner knows exactly where to pick up the baton.

This model isn't just about efficiency; it's about predictability. Goldbeck boasts an annual turnover of over $7.5 billion, constructing more than 600 buildings each year. They've managed to offer what's rare in construction: fixed prices and fixed completion dates. Customers receive not just a building but a promise, much like buying a consumer good with warranties and service contracts. Here, the buildings come with a 5-year service agreement, making the experience of owning a commercial building as straightforward as owning a high-end appliance or vehicle.

The impact of this approach is profound. Goldbeck doesn't just build; they've industrialized building. They've taken the unpredictability out of construction, offering clients the comfort of certainty. This has allowed them to expand their operations across more than 20 European countries, adapting their system to local needs while maintaining their core principles of speed, reliability, and standardization.

In essence, Goldbeck has turned the art of building into a science, where every component, every process, and every employee plays a part in a well-orchestrated symphony of construction. They've made the unpredictable predictable, the custom-made repeatable, and in doing so, have set a new benchmark for what construction can be.

The Vision: A Terafactory

Imagine a world where real estate development was as streamlined and cost-efficient as the production of an iPhone or a Tesla. Enter the concept of a "Terafactory"—a massive, vertically integrated facility dedicated to the production of housing components, engineered with the same precision and efficiency that characterizes the world’s most successful consumer products.

In a Terafactory, every element of a building would be meticulously cost-engineered. Unnecessary components would be eliminated, processes would be automated, and construction would be standardized to the greatest extent possible. Just as Tesla’s Gigafactory revolutionized battery production, the Terafactory will revolutionize housing by mass-producing components in a controlled environment, ensuring consistent quality while dramatically reducing costs.

Goldbeck and Katerra lay the foundation for the next vertical integrator in construction. To those in the industry technology has never meaningfully lived up to its promise. We need a blank slate.

What we are searching for is the next vertical integrator in real estate. The company which posits not an incremental change but a transformational shift in the way we deliver buildings. The more I understand construction the more I realize that we need to build something new from the ground up and incremental change will not transform the industry. Shut it down. Start over.

It’s the only way we can build homes, have children and families, grow and expand our knowledge of the universe; and maybe, one day, even build homes on Mars.