Hi everyone,

This is a weekly newsletter on the intersection of real estate, finance and technology, and specifically how they work together to shape the world around us. Our environment is everything, to stay up to date on what’s driving and crafting it, subscribe here:

Introduction: Unpacking the "Not in My Backyard" Phenomenon

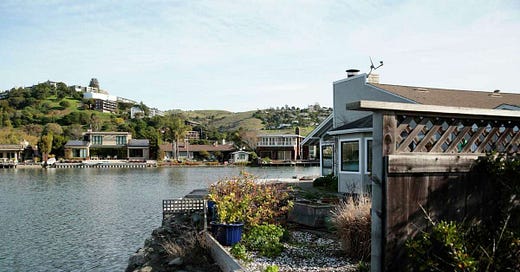

"Wait, they're building what here?" Imagine the surprise that ripples through the scenic neighborhood streets of Belvedere in Marin County, where the median house lists for a casual $4.1 million. The drama over a proposed housing development at Mallard Pointe isn't just local chatter; it's a mirror reflecting America's complex relationship with housing, class, and community. Remember our last

article on how housing can curb inflation? My natural next question was: if this is true, why don’t we just build more? Well, this story dives right into that messy intersection.The Mallard Pointe Saga

First, let's meet our cast and hear their stories. Developer Eric Hohmann and his team are eyeing a 2.8-acre piece of prime land. Their goal? To build a community with 40 new homes, blending 23 apartments, 16 single-family homes, and one accessory dwelling unit. To address the affordability crisis, 12 of these units are slated to be below-market rate. Yet, a year after the application was filed, the city hasn't even scheduled a public hearing for the project. Hohmann's frustration is palpable: "The bureaucracy seems to be moving quite slowly."

While Hohmann waits, a well-funded nonprofit called Belvedere Residents for Intelligent Growth (BRIG) has risen to fight the project. Their rallying cry? More housing equals more problems—think traffic, safety, and the erasure of the local character. The group is raising $30,000 to cover legal fees, posting signs, and even holds nonprofit status. That's right—a nonprofit dedicated to blocking housing, which Hohmann found so shocking he labeled it "flabbergasting."

BRIG's nonprofit status raises an eyebrow or two. Typically, nonprofit status is reserved for entities contributing to the public good—helping the poor, advancing education, etc. When a group like BRIG is able to snag this status while opposing a mixed housing development, the contradictions are glaring. As Riley Hurd aptly puts it, the group's efforts are "the exact opposite of a group of homeowners who recoil at the thought of a dreaded apartment building being put up in their precious community."

A National Issue, Local Manifestation

Let's pan out for a moment. This stand-off isn't unique to Belvedere or even to Marin County, which has been a battleground for housing and environmental concerns for years. According to land-use attorney Riley Hurd, who represents the developers, Mallard Pointe is "the quintessential example of a small wealthy town just making it impossible not just to get a project approved but even to have a hearing." This is a chilling example of how local control can effectively hold new developments—and by extension, societal progress—hostage.

Moreover, if the city can't get its housing plan approved by the California Department of Housing and Community Development, it stands to lose state funding and control over local land use. The state agency isn't impressed so far by Belvedere's efforts. If a well-to-do area like Belvedere can't (or won't) meet state housing expectations, what message does this send to other communities?

Caught in the State Crosshairs: The Clock is Ticking for Belvedere

Let's delve a little deeper into the urgency here. The California Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD) isn't having any of Belvedere's initial housing plans. It's not just a polite suggestion but a state mandate that Belvedere plans for 160 new housing units by 2031. A new consultant has been brought on board to hustle up a viable plan by year's end. The stakes? Lose control over local land use and say goodbye to state funding for transportation and other projects.

What's baffling is the city's initial reliance on backyard cottages, also known as accessory dwelling units (ADUs), to fulfill a whopping 25% of the housing requirements. To put it in perspective, the city has averaged—brace for it—one ADU per year. The state was quick to call this out, noting, "Even the most favorable recent trends would result in a significantly lesser number of accessory units in the planning period."

The town's housing element (AKA “housing plan”), ironically, plans for 47 units at Mallard Pointe while simultaneously stating that the property’s R-2 zoning "prohibits the use of apartment homes." Confused? So is the state, which has explicitly asked Belvedere to clarify this glaring contradiction in the housing element.

Matt Gelfand of Californians for Homeownership bluntly calls Belvedere’s housing element "among the least compliant" in California. Jennifer Silva of the Campaign for Fair Housing Elements echoes this sentiment, terming it "the worst review in Marin so far."

BRIG Chairman John Hansen argues that the proposed Mallard Pointe development isn't aligned with city zoning at all, stating, "Apartments are strictly prohibited in the R-2 zone meant for 'duplex two-family dwellings,' and many of the features and the design of the proposed project don’t conform to our City’s zoning codes and guidelines."

Conclusion: The Mallard Pointe Litmus Test

So here we stand, at an impasse that reverberates far beyond the 66-acre lagoon of Belvedere. The Mallard Pointe development isn't merely a local affair. It asks all of us a challenging question: Who gets to dictate the character of our communities? Do we continue to allow affluent neighborhoods to wall themselves off? Or do we promote a more inclusive vision of community, one where people of different economic backgrounds can coexist?

As Hurd eloquently summarized, it's a question of "when and how we get there." Each community's answer to these questions will not just define their local landscapes but could set precedents that influence broader social values and policies. Navigating this complex terrain requires a nuanced approach, accounting for both the legitimate concerns of existing residents and the broader societal need for more inclusive housing. The choices we make now could either deepen our societal divisions or lay the groundwork for a more inclusive future. It's not just a matter of land and property; it's a reflection of who we are—and who we want to be—as a communities and as a nation.